GraphBLAS and GraphChallenge Advance Network Frontiers

By Jeremy Kepner, David A. Bader, Tim Davis, Roger Pearce, and Michael M. Wolf

Many factors inspire interest in networks and graphs. The Internet is just as important to modern-day civilization as land, sea, air, and space; it connects billions of humans and is heading towards trillions of devices. Deep neural networks (DNNs)—which are also graphs—are key to artificial intelligence, and biological networks underpin life on Earth. In addition, graph algorithms have served as a foundation of computer science since its inception [3]. One can represent and operate on graphs in many different ways. A particularly attractive approach exploits the well-known duality between a graph as a collection of vertices and edges and its representation as a sparse adjacency matrix.

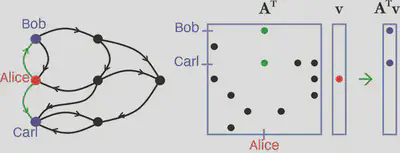

Graph Algorithms in the Language of Linear Algebra, which was published by SIAM in 2011 [6], provides an applied mathematical introduction to graphs by addressing the foundations of graph/matrix duality (see Figure 1). This fundamental connection between the core operations of graph algorithms and matrix mathematics is quite powerful and represents a primary viewpoint for DNNs. Yet despite its widespread use in graph analysis, basic graph/matrix duality is still only a starting point. For instance, the final chapter of Graph Algorithms in the Language of Linear Algebra posed several fundamental questions about the analysis of large graphs in ontology/data modeling; time evolution (or streaming); detection theory (or graph modeling in general); and algorithm scaling [6]. These questions—along with the emergence of important applications in privacy, health, and cyber contexts—set the stage for the subsequent decade of work.

Since 2011, researchers have written thousands of papers that explore the aforementioned topics from a graph/matrix perspective. Interestingly, previous prototyping efforts that began in the mid-2000s recognized that existing computer architectures were not a good match for a variety of graph and sparse matrix problems [10]. The prototypes introduced several innovations: high-bandwidth three-dimensional networks, cacheless memory, accelerator-based processors, custom low-power circuits, and—perhaps most importantly—a sparse matrix-based graph instruction set. Today, many of these innovations are present in commercially available systems like Cerebras, Graphcore, Lucata, and NVIDIA.

The challenges associated with graph algorithm scaling led multiple scientists to identify the need for an abstraction layer that would allow algorithm specialists to write high-performance, matrix-based graph algorithms that hardware specialists could then design to without having to manage the complexities of every type of graph algorithm. With this philosophy in mind, a number of researchers (including two Turing Award winners) came together and proposed the idea that “the state of the art in constructing a large collection of graph algorithms in terms of linear algebraic operations is mature enough to support the emergence of a standard set of primitive building blocks” [8]. The centerpiece of this abstraction is the extension of traditional matrix multiplication to semirings

C=AB=A⊕.⊗B

where A, B, and C are (usually sparse) matrices over a semiring with corresponding scalar addition ⊕ and scalar multiplication ⊗. Particularly interesting combinations include standard matrices over real or complex numbers (+.x), tropical algebras (max.+) that are important for neural networks, and set operations (∪.∩) that form the foundation of relational databases like SQL. One can build countless graph algorithms with these combinations of operations, and the Graph Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms (GraphBLAS) mathematical specification, C specification, and high-performance implementation subsequently emerged [1, 4, 5]. These programs are now part of some of the world’s most popular mathematical software environments.

Many innovations in graph processing occurred during this time, inspiring new venues to highlight these developments. MIT, DARPA, Amazon, IEEE, and SIAM collaborated to establish GraphChallenge, which consists of several hundred data sets and well-defined mathematical graph problems in the areas of triangle counting, clustering of streaming graphs, and sparse DNNs. Since its debut in 2017, GraphChallenge has seen an abundance of submissions — contestants have even integrated parts of their work into a wide range of research programs and system procurements.

GraphChallenge has revealed that due to resulting improvements in graph analysis systems, many graph problems are now fundamentally bound by computer memory bandwidth (as opposed to processor speed or memory latency) [9]. It has also provided clear targets for those who are trying to advance computing systems scaling for the solution of graph problems. Additionally, innovations to improve the performance of graph algorithms have fed back into sparse linear algebra libraries to benefit scientific computing applications like Kokkos Kernels [11].

Questions in ontology/data modeling pertain to the way in which researchers handle more diverse data. The data that we want to manage with graphs involve more than just simple vertices and edges; they often include a large variety of very diverse metadata that are stored in SQL and NoSQL databases. Unsurprisingly, many folks in the database community have also been working on graph databases. To mathematically encompass these concepts, we must generalize the idea of a matrix into something called an associative array. For example, one can view a matrix as a mapping

A:I×J→V

where I={1,…,M}, J={1,…,N}, and V is complex. In an associative array, I and J are now any strict totally ordered set (e.g., a set of strings) and V is a semiring [7]. This concept was first implemented in the D4M software system, which links matrix mathematics and databases. It is now present in a number of database systems that utilize GraphBLAS as their underlying mathematical engine [2].

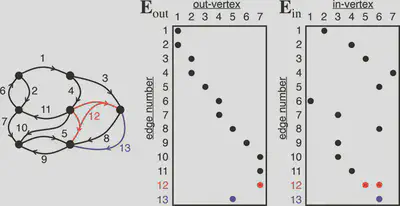

Time-evolving or streaming graphs have become one of the most important problems in graph analysis, and GraphBLAS has a natural way of addressing streaming graphs with diverse data via edge (or incidence) matrices (see Figure 2). Traditional adjacency matrices are limited in the types of graphs that they can represent. Adjacency matrices typically represent directed weighted graphs—which are a very important class of problems—but real data tend to be much more dynamic and diverse, with multiple edges and hyper-edges (edges that are connected to multiple vertices). In an edge matrix representation, one can easily adjust for this type of graph by simply adding rows to the end of the matrix. Furthermore, researchers can compute the corresponding adjacency matrix via

A=EoutTEin

where T denotes the matrix transpose.

Ultimately, the aforementioned capabilities—enabled by GraphBLAS along with other graph innovations that are highlighted by GraphChallenge—have yielded new tools for tackling some of the most difficult and important problems in health data, privacy-preserving analytics, cybersecurity, and DNNs.

References

[1] Buluç, A., Mattson, T., McMillan, S., Moreira, J., & Yang, C. (2017). Design of the GraphBLAS API for C. In 2017 IEEE international parallel and distributed processing symposium workshops (IPDPSW). Lake Buena Vista, FL: IEEE.

[2] Cailliau, P., Davis, T., Gadepally, V., Kepner, J., Lipman, R., Lovitz, J., & Ouaknine, K. (2019). RedisGraph GraphBLAS enabled graph database. In 2019 IEEE international parallel and distributed processing symposium workshops (IPDPSW). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: IEEE.

[3] Cormen, T.H., Leiserson, C.E., Rivest, R.L., & Stein, C. (2022). Introduction to algorithms (4th ed). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[4] Davis, T.A. (2019). Algorithm 1000: SuiteSparse:GraphBLAS: Graph algorithms in the language of sparse linear algebra. ACM Transact. Math. Software, 45(4), 1-25.

[5] Kepner, J., Aaltonen, P., Bader, D., Buluç, A., Franchetti, F., Gilbert, J., … Moreira, J. (2016). Mathematical foundations of the GraphBLAS. In 2016 IEEE high performance extreme computing conference (HPEC). Waltham, MA: IEEE.

[6] Kepner, J., & Gilbert, J. (Eds.) (2011). Graph algorithms in the language of linear algebra. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

[7] Kepner, J., & Jananthan, H. (2018). Mathematics of big data: Spreadsheets, databases, matrices, and graphs. In MIT Lincoln Laboratory Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[8] Mattson, T., Bader, D., Berry, J., Buluç, A., Dongarra, J., Faloutsos, C., … Yoo, A. (2013). Standards for graph algorithm primitives. In 2013 IEEE high performance extreme computing conference (HPEC). Waltham, MA: IEEE.

[9] Samsi, S., Kepner, J., Gadepally, V., Hurley, M., Jones, M., Kao, E., … Monticciolo, P. (2020). GraphChallenge.org triangle counting performance. In 2020 IEEE high performance extreme computing conference (HPEC). Waltham, MA: IEEE.

[10] Song, W.S., Kepner, J., Nguyen, H.T., Kramer, J.I., Gleyzer, V., Mann, J.R., … Mullen, J. (2010). 3-D graph processor. Presented at the fourteenth annual high performance embedded computing workshop (HPEC 2010). Lexington, MA: MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

[11] Trott, C., Berger-Vergiat, L., Poliakof, D., Rajamanickam, S., Lebrun-Grandie, D., Madsen, J., … Womeldorff, G. (2021). The Kokkos EcoSystem: Comprehensive performance portability for high performance computing. Comput. Sci. Eng., 23(5), 10-18.

Jeremy Kepner is head and founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory’s Supercomputing Center, a founder of the MIT-Air Force AI Accelerator, and a founder of the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center, with appointments in MIT’s Department of Mathematics and MIT Connection Science. He is a SIAM Fellow. David A. Bader is a distinguished professor and founder of the Department of Data Science in the Ying Wu College of Computing, as well as director of the Institute for Data Science at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. He is a SIAM Fellow. Tim Davis is a professor of computer science and engineering at Texas A&M University. He is also a SIAM Fellow. Roger Pearce is a computer scientist in the Center for Applied Scientific Computing at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and an adjunct Computer Science and Engineering Associate Professor of Practice at Texas A&M University. Michael M. Wolf manages the Scalable Algorithms Department at Sandia National Laboratories.

https://sinews.siam.org/Details-Page/graphblas-and-graphchallenge-advance-network-frontiers