Linux and Supercomputing: How my passion for building COTS systems led to an HPC revolution

In the 1990s I designed and built the first Linux supercomputer that remains the foundational infrastructure of today’s Linux supercomputers, including the fastest machines in the world. The ease of use of Linux supercomputers has had a profound impact on how scientists conduct their research and on the most pressing issues of our time, and I am proud of my role in this revolution in computing and discovery. Whether they are simulating astrophysical phenomena, impacts of climate change, or biological functions at the cellular level, Linux supercomputers are today’s primary tool of knowledge discovery. Here I present my development of the first bona fide Linux supercomputer. Today, researchers are building a new generation of exascale computing systems – machines capable of calculating at least one quintillion floating point operations per second. The Linux operating system is intrinsic to this effort because it provides the scale and flexibility to support high-performance computing at the exascale level.

Back in the early 1990s when I was a graduate student in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Maryland, the term “supercomputer” meant Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) vector processor machines (the Cray-1 was the most popular), or massively parallel multiprocessor systems, such as the Thinking Machine CM-5. These systems were bulky—a Cray-1 occupied 2.7m by 2m of floor area and contained 60 miles of wires1; expensive, selling for several million dollars; and required significant expertise to program and operate. Supercomputing was mainly a function of the U.S. Department of Defense and its Soviet counterpart, large government and academic labs, and large industrial users. Each system used its own proprietary software and none was compatible with any other.

But something new was on the horizon—a revolution in supercomputing technology was beginning that would bring scalable, less expensive systems to a much wider audience. That revolution involved using a new, open-source, operating system called Linux and collections of commodity off-the shelf (COTS) servers to obtain the performance of a traditional supercomputer. I was deeply involved with that revolution from the start. In 1989, as an undergraduate student at Lehigh University, I built my first parallel computer, using several Commodore Amiga 1000 personal computers that the company had donated to Lehigh. They had been collecting dust in a closet when a friend and I networked them together. A year later, I designed parallel algorithms on a 128-processor nCUBE hypercube parallel computer donated by AT&T Bell Laboratories. Building these systems taught me that the development of powerful parallel machines required a simultaneous development of scalable, high performance algorithms and services. Otherwise, application developers would be forced to develop algorithms from scratch every time vendors introduced a newer, faster, hardware platform.

By the late 1990s, the term “cluster computing” was common among computer science researchers and several of these systems had received significant publicity. One of the first cluster approaches to attract interest was Beowulf, which cost from a tenth to a third of the price of a traditional supercomputer. A typical setup consisted of server nodes, with each one controlling a set of client nodes connected by Ethernet and running the Linux operating system2. In the spring of 1998, Los Alamos National Laboratory introduced a more powerful version of Beowulf called Avalon, using 68 personal computers running on DEC Alpha microprocessors3. However, neither the Beowulf cluster nor Avalon were genuine supercomputers, for they could not deliver high performance across the broad set of applications that ran on contemporary supercomputers.

The Beowulf project was not about developing a supercomputer per se, but rather aimed to “explore the potential of ‘Pile-of-PCs’” at the lowest possible cost and develop methods for applying these systems to NASA Earth and space science problems4. As Thomas Sterling, co-creator of the first Beowulf cluster, observed, “Basically, you can order most of Beowulf’s components from the back pages of Computer Shopper or get them for free over the ‘Net.”5 Beowulf clusters were limited to solving problems that could be neatly divided into independent tasks, because the communication among processors required to run massively parallel applications on supercomputers did not exist yet.

Avalon was powerful enough to make it onto the “Top500 List” of supercomputers in 1998, but although the system was fast, it was not truly a supercomputer. As a Beowulf cluster that could run several applications, Avalon’s nodes were connected via Ethernet and utilized message passing over TCP, which meant relatively low bandwidth, high latency, and serious performance issues when executing parallel programs. Avalon made the list based on its ability to run the LINPACK benchmark. But its limited connectivity meant it could only run applications with a minimal need for communication as well as some domain decomposition methods, where performance is based almost entirely on processor speed.

From Experimental Clusters to the first bona fide Linux Supercomputer

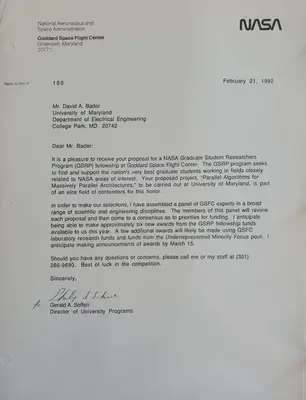

Less attention has been focused on parallel computing systems using COTS components and open-source operating systems that were developed before Avalon and Beowulf. Building these systems was my passion. In January 1992, I joined the University of Maryland as an electrical and computer engineering doctoral student and visited the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in search of fellowships in parallel computing. In August, I received the NASA Graduate Student Researcher Fellowship and built my first parallel computer using Ethernet-connected, Intel-based PCs and the FreeBSD operating system in 1993, prior to the Beowulf project. After receiving my Ph.D. in May 1996, over the next eighteen months I was a postdoc at the university and a National Science Foundation (NSF) research associate at its Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS). In this role, I built an experimental computing cluster comprising 10 DEC AlphaServer nodes, each with four DEC Alpha RISC processors and a DEC PCI card connected to a DEC Gigaswitch ATM switch. It used either my own communication library or a freely available MPI implementation. This system was more advanced than Los Alamos National Laboratory’s (LANL) Avalon cluster, which used Fast Ethernet for interconnection rather than an ATM network with lower latency and higher throughput.6

The National Computational Science Alliance and Roadrunner

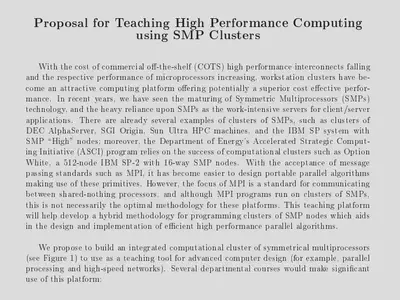

From Maryland, in January 1998 I moved to the University of New Mexico and the Albuquerque High Performance Computing Center (AHPCC). There I had the opportunity to build and deploy, to my knowledge, the first bona fide Linux supercomputer while continuing to develop clusters of COTS processors into systems with the speed, performance, and services of a traditional supercomputer. I came to UNM with the idea of building the first x86 Linux supercomputer as a teaching tool for advanced computer design. My system design took a revolutionary new direction that differed significantly from Beowulf and the HPC research community’s cluster efforts. From my experience with real applications, I knew that Beowulf did not have the capabilities to run the broad set of scientific computing tasks on contemporary supercomputers, and more engineering was necessary to create a Linux-based system that would displace traditional supercomputers.

While Beowulf optimized to minimize cost per megaFLOP and required only free software, my system design maximized performance per price per megaFLOP, and used both mass market commodity components and proprietary software and networks. Beowulf used only Ethernet for the system area network, and I engineered the first use of a proprietary scalable network, Myrinet, in a Linux system since communication was often an HPC bottleneck. Instead of a single network, Ethernet, my system design used three: a control network (Fast Ethernet with Gigabit Ethernet uplinks); a highly scalable data network (Myrinet switches); and a diagnostic network (chained RS-232 serial ports) to monitor the nodes for failures, provide staged boot up of systems, and enable remote power cycling capabilities for system maintenance. Donald Becker, co-founder of the Beowulf project, advocated for clusters that combined “independent machines…. With a cluster, you have the opportunity to incrementally scale, where an SMP is generally built to a [preconfigured] size.”7 I argued for and built clusters of SMP nodes.

After becoming the sole principal investigator [PI] for the AHPCC’s SMP Cluster Computing Project, by spring 1998 I had built the first working Intel/Linux supercomputer using an Alta Technologies “AltaCluster,” consisting of eight dual, 333 MHz, Intel Pentium II nodes. This required my porting of software to Linux to provide necessary components; modifying the Linux kernel and shell to increase space for very large command lines; and porting the codes from members of the National Computational Science Alliance (NCSA) to Linux—none had run on Linux previously. My work also included a partnership with Myricom’s president and CEO Chuck Seitz to incorporate the first Myrinet interconnection network for Intel/Linux. I also ported a job scheduler, the Portable Batch System developed at NASA Ames Research Center, to the Linux system and installed RedHat’s “Extreme Linux” before its widespread distribution that May.8

Around this time, I also became a PI with the NCSA, an NSF-supported effort to integrate computational, visualization, and information resources into a national-scale “Grid.”9 NSF and NCSA, led by Larry Smarr, made a high risk, high payoff bet in my vision of the first Linux supercomputer widely available to national science communities by allocating US$400,000, based on demonstrations of my 1998 16-processor Linux machine prototype. I assembled a team and we built Roadrunner, which entered production mode in April 1999. Its hardware comprised fully configured workstations powered by 128 dual, 450 MHz, Intel Pentium II processors; a 512 KB cache; a 512 MB SDRAM with ECC; 6.4 GB IDE hard drive; and Myrinet interface cards. The Myrinet System Area Network (Myrinet/SAN) interconnection network was one of Roadrunner’s main improvements over previous Linux systems, such as Beowulf and Avalon. At full-duplex 1.28 GB/s bandwidth, it was twice as fast as Myrinet/LAN and about five times faster than Ethernet, with much lower latency: in the tens of microseconds. Roadrunner’s system software included the Red Hat Linux 5.2 operating system; sets of compilers from both the GNU Compiler Collection and the Portland Group; and the Portable Batch System (PBS) job scheduler originally designed for NASA’s supercomputers. These features enabled parallel programming, such as software-based distributed shared memory (DSM) and the Message Passing Interface (MPI), a standardized means of exchanging information between multiple computer nodes. For MPI, Roadrunner used MPICH, a high performance open-source MPI implementation from Argonne National Laboratory; Myricom GM network drivers; and MPICH GM, Myricom’s MPI implementation.

Roadrunner was among the 100 fastest supercomputers in the world when it went online. It provided services that were lacking in the first Linux clusters but are now regarded as essential for supercomputing, such as node-based resource allocation, job monitoring and auditing, and resource reservations.10 At the time, Roadrunner was dubbed a supercluster, combining the low cost and accessibility of Linux clusters with the services, fast networking, and low latency of a supercomputer. It was however one of the Alliance’s first hardware deployments designed to bring supercomputing to the desktop. Roadrunner went on to become a node on the National Technology Grid.

The Grid was envisioned as a way to give researchers access to supercomputers for large-scale problem solving from their desktops, no matter their location, through the nation’s fastest high-performance research networks. Alliance Director Larry Smarr likened the National Technology Grid to the power grid, where users could plug in and get the compute resources they needed, without having to worry about where those resources came from or their own location.

Within the Alliance, computer scientists and software and hardware engineers worked closely with domain scientists to ensure that the systems being developed would meet the requirements of scientists needing supercomputers to solve complicated scientific problems. Scientific software that ran on Roadrunner included AZTEC, algorithms for solving sparse systems of linear equations; BEAVIS (Boundary Element Analysis of Viscous Suspensions), used for 3-D analysis of multiphase flows; Cactus, a numerical relativity toolkit for solving astrophysics problems; HEAT, a diffusion partial differential equation using conjugate gradient solver methods; HYDRO, a Lagrangian hydrodynamics code; and MILC, a set of codes developed by the MIMD Lattice Computation collaboration to study quantum chromodynamics.

Roadrunner’s performance on the Cactus application benchmark showed near perfect scalability, unlike systems such as the NASA Beowulf cluster, the NCSA’s Microsoft Windows NT cluster computer, and Silicon Graphics Inc.’s family of high-end server computers, the Origin 2000. Several scientists who pioneered the use of the Roadrunner system shared their memories:

“It was a very exciting time; Linux clusters were emerging as a huge force to democratize supercomputing and software frameworks providing community toolkits to solve broad classes of science and engineering problems were also taking shape. The collaboration we had between the Cactus team at the Albert Einstein Institute in Germany and David Bader’s team with the Roadrunner supercluster was a pioneering effort that helped these movements gain traction around the world. The collaboration helped advance the goals of the Cactus team, led by Gabrielle Allen, whose efforts continue to this day as the underlying framework of the Einstein Toolkit. That toolkit now powers many efforts globally to address complex problems in multi-messenger astrophysics.”

— Edward Seidel, Ph.D. President, University of Wyoming Former Head of the Numerical Relativity and E-Science Research Groups, Albert Einstein Institute

“We tested our large weather prediction codes on Roadrunner and found it to be a powerful platform for code development and application, with the move to COTS hardware and software opening the doors to non-proprietary clusters for many researchers who until then only did their work on workstations and laptops. The Roadrunner network (Message Passing Interface) results were superior to those from previous clusters’ Ethernets in moving data from one processor to another during a weather forecast, thus enhancing the forecast turnaround time or forecast quality by allowing for more grid points to be used and a correspondingly more resolved weather feature prediction. We also used Roadrunner to produce detailed simulations of thunderstorms and turbulence generated at commercial airline flight levels.”

—Dan Weber Retired Research Meteorologist

and

—Kelvin Droegemeier, Ph.D. OU Regents Professor of Meteorology Weathernews Chair Emeritus Roger and Sherry Teigen Presidential Professor Former Director, White House Office of Science and Technology Policy

“Roadrunner, to my knowledge, was the first Linux cluster-based supercomputer available to the research community. It was a forerunner of what has become a dominant approach in supercomputing. In 1999, while just starting at MIT, I was able to obtain access to Roadrunner to test and scale a number of key parallel software technologies, which formed the basis of establishing our supercomputing center at MIT. This early work pioneered on Roadrunner impacts thousands of researchers across MIT.”

—Jeremy Kepner, Ph.D. Head and Founder, MIT Lincoln Laboratory Supercomputing Center

The development of the first Linux supercomputer had effects far beyond the needs of Alliance scientists. It permanently changed supercomputing and its impacts are still felt today.

The Continuing Linux Supercomputing Revolution

As leader of the Alliance/UNM Roadrunner project, I presented my team’s work at professional events, such as the Alliance Chautauquas held at UNM, the University of Kentucky, and Boston University in 1999.1112 After Roadrunner, I embarked on another Alliance project, working with IBM on development of LosLobos, IBM’s first Linux production system, which was assembled and operated at the University of New Mexico. LosLobos, which premiered on the Top500 list at number 24, consisted of 256 dual processor, Intel-based, IBM servers with Myrinet connections, creating a 512-processor machine capable of 375 gigaFLOPs.

LosLobos entered production in summer 2000. The Linux supercomputing movement was well underway, thanks to the proliferation of commodity components, the development of high-speed COTS networks such as Myrinet, the rapid expansion of the open software movement, and the ability of researchers, myself included, to exploit all these developments. For the first time, supercomputers could be built at a relatively low cost. While LosLobos was used primarily by scientists to model and solve complicated problems in physics, biology, and other fields, IBM’s move toward the open-source framework was a sign of things to come. Within a year, it used the knowledge gained by working with my Alliance research group on LosLobos to create the first pre-assembled and pre-configured Linux server clusters for business.13

Today, all supercomputers on the Top500 list are Linux systems. Simply put, today’s machines are no longer purpose-built monoliths. Using an open-source operating system, running on commodity microprocessors, and networked with high-speed commodity interconnects, Linux cluster supercomputers can be easily customized for different uses, unlike vendor-specific Unix systems. They provide users speed, high-end services, and unprecedented flexibility, all at a lower cost than in traditional supercomputers. They can also be integrated into any datacenter, making feasible enterprise systems that are similar to those breaking scientific barriers.

The ease of use of Linux supercomputers has had a profound impact on how scientists conduct their research and on the most pressing issues of our time, and I am proud of my role in this revolution in computing and discovery. Whether they are simulating astrophysical phenomena, the impacts of climate change, or biological functions at the cellular level, Linux supercomputers are today’s primary tool of knowledge discovery.

Today, researchers are building a new generation of exascale computing systems – machines capable of calculating at least 1018 floating point operations per second (1 exaFLOPS). The Linux operating system is intrinsic to this effort because it provides the scale and flexibility to support high-performance computing at the exascale level. The framework that I developed in the 1990s remains the foundational infrastructure of today’s Linux supercomputers, including the fastest machines in the world.

For me, this is both thrilling and gratifying. My interest in parallel computing dates to 1981, when I read an article on a parallel computing system for image processing and pattern recognition14. I’ve spent my entire career making Linux-based COTS systems a viable and more affordable alternative to traditional supercomputers. I’ve incorporated popular compilers, job schedulers, and MPICH to COTS Linux deployments, and those innovations are still used today on Linux supercomputers, enabling Linux to become the OS of choice on high performance machines.

Exascale supercomputers will provide unprecedented capability to integrate data analytics, AI, and simulation for advanced 3-D modeling. They will tackle problems related to neuroscience, nuclear fusion, the biology of cancer, and will give nations a competitive edge in energy R&D and national security. It is my hope that somewhere a young computer scientist is reading my published work and it is sparking the same inspiration in them as Siegel’s work inspired in me. My work has become one of the building blocks of 21st-century computing technologies, and I look forward to seeing how others build on my innovations with their own.

About the Author:

David A. Bader is a distinguished professor in the department of data science in the Ying Wu College of Computing and Director of the Institute for Data Science at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. Prior to this, he served as founding professor and chair of the School of Computational Science and Engineering, College of Computing, at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is a Fellow of the IEEE, AAAS, and SIAM.

© 2021 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, collecting new collected works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works.

Additional Documents

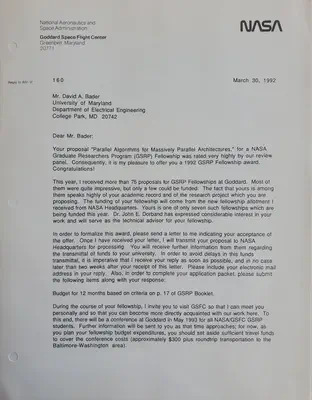

NASA Graduate Student Researchers Program (GSRP) Letter from Dr. Gerald A. Soffen, Director of University Programs, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (21 February 1992):

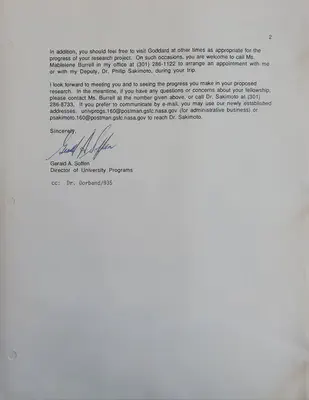

NASA Award Letter from Dr. Gerald A. Soffen (30 March 1992):

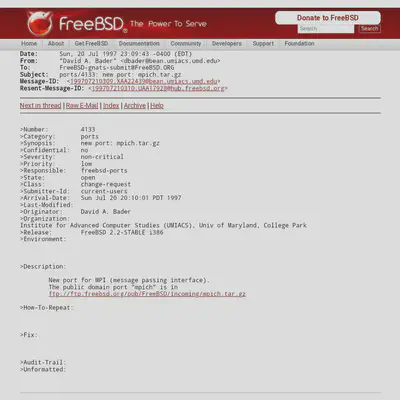

FreeBSD MPI port (20 July 1997):

Invitation to RoadRunner Dedication, Reception, and Dinner (8 April 1999):

History of Cray Supercomputers. Hewlett Packard Enterprise, www.hpe.com/us/en/compute/hpc/cray.html , accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

Sterling, T., D. Savarese, D. Becker, J. Dorband, U. Ranawake and C. V. Packer. “BEOWULF: A Parallel Workstation for Scientific Computation.” Proc. 24th Int. Conf. on Parallel Processing (1995), p. 11-14. ↩︎

“Linux and Supercomputers.” Linux Journal, www.linuxjournal.com/content/linux-and-supercomputers , November 29, 2018, accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

D. Ridge, D. Becker, P. Merkey, and T. Sterling, “Beowulf: harnessing the power of parallelism in a pile-of-PCs,” 1997 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Snowmass, CO, USA, 1997, Vol. 2, pp. 79-91, https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.1997.577619 . ↩︎

Supercomputing gets a new Hero,” Communications News, August 1, 1998, www.thefreelibrary.com/Supercomputing+gets+a+new+hero-a021071072 , accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

D. Bader and J. JáJá, “SIMPLE: A Methodology for Programming High Performance Algorithms on Clusters of Symmetric Multiprocessors (SMPs).” Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 58(1): 92-108, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1006/jpdc.1999.1541 . ↩︎

Joab Jackson, “Donald Becker: The inside story of the Beowulf saga,” GCN, 13 April 2005, https://gcn.com/articles/2005/04/13/donald-becker--the-inside-story-of-the-beowulf-saga.aspx , accessed 21 July 2021. ↩︎

“Announcing Extreme Linux,” www.redhat.com/en/about/press-releases/press-extremelinux , May 13, 1998, accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

“The Grid links the Alliance together and provides access to its wide variety of resources to the national scientific research community. Using high performance networking, the Grid will link the highest performing systems to mid-range versions of these architectures, and then to the end users’ workstations, thereby creating a national Power-Grid.”: “National Computational Science Alliance,” 1997-2005, National Science Foundation Award #9619019, www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=9619019 , accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

D. A. Bader, A. B. Maccabe, J. R. Mastaler, J. K. McIver, and P. A. Kovatch, “Design and Analysis of the Alliance/University of New Mexico Roadrunner Linux SMP SuperCluster,” IEEE Computer Society International Workshop on Cluster Computing (IWCC), Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1999, pp. 9-18, https://doi.org/10.1109/IWCC.1999.810804 . ↩︎

D.A. Bader, “CLUSTERS - The Most Rapidly Growing Architecture of High-End Computing,” https://web.archive.org/web/20000203101440/http://chautauqua.ahpcc.unm.edu/agenda.html , archived from the original on 3 February 2000, accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

“Chautauquas Revive an American Forum for a New Era,” Aug. 4, 1999. https://davidbader.net/post/19990804-chautauqua/ , accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

“IBM unveils pre-packaged Linux clusters,” www.computerweekly.com/news/2240043115/IBM-unveils-pre-packaged-Linux-clusters , November 14, 2001, accessed 8 July 2021. ↩︎

H. J. Siegel, L. J. Siegel, F. C. Kemmerer, P. T. Mueller, H. E. Smalley and S. D. Smith, “PASM: A Partitionable SIMD/MIMD System for Image Processing and Pattern Recognition,” IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. C-30, no. 12 (Dec. 1981), pp. 934-947, https://doi.org/10.1109/TC.1981.1675732 . ↩︎