What Exactly Is a 'Flop,' Anyway?

President Obama’s call for exaflop supercomputing is as good a time as any to talk about floating-point operations per second.

By Michael Byrne

Earlier this week, President Obama signed an executive order creating the National Strategic Computing Initiative, a vast effort at creating supercomputers at exaflop scales. Cool. An exaflop-scale supercomputer is capable of 1018 floating point operations (FLOPS) per second, which is a whole lot of FLOPS.

But this raises the question: What’s a floating point operation and why does it matter so much to supercomputing when our mere mortals of computers are rated according to the simple-seeming notion of clock speed? I haven’t the faintest idea how many FLOPS this Lenovo might be capable of (though, as we’ll see, it can certainly be calculated).

David Bader, chair of the Georgia Institute of Technology School of Computational Science and Engineering, suggests we “think of flops similar with horsepower to a car.” In buying the family Subaru (or whatever), you’re interested in a whole list of different metrics: gas mileage, safety rating, reliability. But, if it’s a racecar in question, e.g. a car that will do nothing but race around a track at top speed, the requirements are a lot more about horsepower, which is the thing wins races.

So, the answer has to do with the difference in how your own computer and an extremely high-performance supercomputer are used. The latter is used for doing incredibly vast mathematical calculations while consumer computers are designed to run stuff like the browser you’re currently reading this in. The key thing is that the browser’s operation is all about your input and input from the internet itself. A browser spends a lot of time waiting around, in other words. And the same goes for most of the computing you do: it’s input/output based.

The distinction might not be very intuitive. What it means is that the computer programs you’re used to running (or the sub-programs within those programs) are always stalling as they wait for other sub-programs (functions, methods, routines) and programs to finish or for some piece of input to arrive. We call this kind of computing sequential. Things happen only after other things have completed and the whole mess is characterized by complex inter-dependencies. What it looks like is logical decision making: if … then, not, and, or, etc.

Mathematical computation is in general a different sort of beast, for a couple of connected reasons. The first is that it’s usually easy to do it using parallel, rather than sequential, processing. Big computations can often be broken down into smaller and smaller, easier and easier computations. Which means they can spread around to a bunch of different processors all working simultaneously. This is why GPUs are now becoming much more than graphics processing units—they exploit parallelism. Parallelism used to be useful largely for image rendering (where individual pixels can be operated on individually), but as computing becomes more and more data-focused, the idea has become much more general. So have GPUs.

So, in a sense, you can imagine a GPU as a consumer-scale supercomputer. There’s another characteristic of mathematical/scientific computing that sets it apart, however. This is just the nature of the numbers themselves, or their precision. Computing numbers more precise than whole numbers is a very different process.

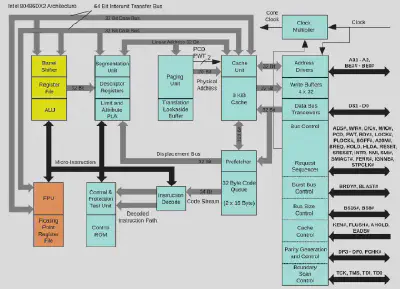

This is so much so that it occurs on its very own dedicated hardware. A CPU is built to operate on integers—whole numbers. Which is fine because it’s not so much doing math as using numbers to model/implement the execution of a program that probably isn’t a scientific calculator. But, that said, most any general purpose computer is going to need to calculate non-integer numbers—more properly known as floating point numbers—on a regular basis.

This can’t be accomplished on a CPU because floating point numbers are represented by computers in a very, very different way. An integer value described by a string of binary digits is just a simple base conversion. The numbers we use every day, which are somewhat confusingly referred to as decimal numbers even if they don’t employ a decimal point, are represented in a base-10 counting system. This “10” is actually where the “decimal” of a decimal number or decimal point comes from. Every digit in a decimal number corresponds to a value of that digit multiplied by 10 raised to the position of that digit. So, the number 12 is 2 * 100 + 1 * 101 and so forth. That’s the base-10 counting system. With binary, every digit is just 2 raised to the digit’s position times either a 1 or a 0. So, given a decimal number, I can turn it into a binary number and vise versa just through some simple arithmetic.

If I tried the same thing with a floating point number, it wouldn’t work out at all. In a floating point number, digits mean very particular things. Some digits correspond to the actual digits of the number, some correspond to the base we’re using to represent that number, and some correspond to where exactly in the number we should place a decimal point. In a sense, every floating point number must be decoded according to a small set of rules. Treat it in any other way and the number is just nonsense.

This is why floating point numbers are computed on different hardware, which is known as a floating-point unit. An FPU is very much so built for long mathematical operations. It’s possible to take the longest formula you can imagine, populated by the longest data set, and rearrange it a bit such that it can be fed through a floating-point unit in a really natural way. This is why when we talk about supercomputing, a land of deep mathematical problems and deep simulations based on mathematical problems, it’s useful to talk about floating-point speeds.

Floating-point numbers and parallel computations come together in how FLOPS are calculated. The basic idea is to take the number of floating-point calculations that can be performed in a single processor clock cycle (four, usually) multiply it by the processor’s clock speed and then scale it by the number of available cores per socket connecting them. In the simplest case of a single core architecture operating at 2.5 GHz, we’ll wind up with 10 billion (2.5 GHz * 4) FLOPS.

So, based on the calculation above, it’s possible to increase FLOPS without increasing processor clock speeds, which is good news for supercomputing if not for your MacBook. “You’ll notice that clock speed hasn’t been increasing significantly in the last decade on consumer machines,” Bader says, “because we’re hitting the limits of chip technology. Instead, we see chip makers like Intel, IBM, and NVIDIA, moving towards parallelism such as multicore and manycore processors.”

Parallel programming hasn’t quite become mainstream, and it will always be constrained by the percentage of a given computer program that must execute sequentially, but FLOPS increasingly matter, if not always at exascales.

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vvbajx/what-exactly-is-a-flop-anyway