Feds Look to Fight Leaks with 'Fog of Disinformation'

By Noah Shachtman

Pentagon-funded researchers have come up with a new plan for busting leakers: Spot them by how they search, and then entice the secret-spillers with decoy documents that will give them away.

Computer scientists call it it “Fog Computing” – a play on today’s cloud computing craze. And in a recent paper for Darpa, the Pentagon’s premiere research arm, researchers say they’ve built “a prototype for automatically generating and distributing believable misinformation … and then tracking access and attempted misuse of it. We call this ‘disinformation technology.’”

Two small problems: Some of the researchers’ techniques are barely distinguishable from spammers’ tricks. And they could wind up undermining trust among the nation’s secret-keepers, rather than restoring it.

The Fog Computing project is part of a broader assault on so-called “insider threats,” launched by Darpa in 2010 after the WikiLeaks imbroglio. Today, Washington is gripped by another frenzy over leaks – this time over disclosures about U.S. cyber sabotage and drone warfare programs. But the reactions to these leaks has been schizophrenic, to put it generously. The nation’s top spy says America’s intelligence agencies will be strapping suspected leakers to lie detectors – even though the polygraph machines are famously flawed. An investigation into who spilled secrets about the Stuxnet cyber weapon and the drone “kill list” has already ensnared hundreds of officials – even though the reporters who disclosed the info patrolled the halls of power with the White House’s blessing.

That leaves electronic tracking as the best means of shutting leakers down. And while you can be sure that counterintelligence and Justice Department officials are going through the e-mails and phone calls of suspected leakers, such methods have their limitations. Hence the interest in Fog Computing.

The first goal of Fog Computing is to bury potentially valuable information in a pile of worthless data, making it harder for a leaker to figure out what to disclose.

“Imagine if some chemist invented some new formula for whatever that was of great value, growing hair, and they then placed the true [formula] in the midst of a hundred bogus ones,” explains Salvatore Stolfo, the Columbia University computer science professor who coined the Fog Computing term. “Then anybody who steals the set of documents would have to test each formula to see which one actually works. It raises the bar against the adversary. They may not really get what they’re trying to steal.”

The next step: Track those decoy docs as they cross the firewall. For that, Stolfo and his colleagues embed documents with covert beacons called “web bugs,” which can monitor users’ activities without their knowledge. They’re popular with online ad networks. “When rendered as HTML, a web bug triggers a server update which allows the sender to note when and where the web bug was viewed,” the researchers write. “Typically they will be embedded in the HTML portion of an email message as a non-visible white on white image, but they have also been demonstrated in other forms such as Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents.”

“Unfortunately, they have been most closely associated with unscrupulous operators, such as spammers, virus writers, and spyware authors who have used them to violate users privacy,” the researchers admit. “Our work leverages the same ideas, but extends them to other document classes and is more sophisticated in the methods used to draw attention. In addition, our targets are insiders who should have no expectation of privacy on a system they violate.”

Steven Aftergood, who studies classification policies for the Federation of American Scientists, wonders whether the whole approach isn’t a little off base, given Washington’s funhouse system for determining what should be secret. In June, for example, the National Security Agency refused to disclose how many Americans it had wiretapped without a warrant. The reason? It would violate Americans’ privacy to say so.

“If only researchers devoted as much ingenuity to combating spurious secrecy and needless classification. Shrinking the universe of secret information would be a better way to simplify the task of securing the remainder,” Aftergood tells Danger Room in an e-mail. “The Darpa approach seems to be based on an assumption that whatever is classified is properly classified and that leaks may occur randomly throughout the system. But neither of those assumptions is likely to be true.”

Stolfo, for his part, insists that he’s merely doing “basic research,” and nothing Pentagon-specific. What Darpa, the Office of Naval Research, and other military technology organizations do with the decoy work is “not my area of expertise,” he adds. However, Stolfo has set up a firm, Allure Security Technology Inc., “to create industrial strength software a company can actually use,” as he puts it. That software should be ready to implement by the end of the year.

It will include more than bugged documents. Stolfo and his colleagues have also been working on what they call a “misbehavior detection” system. It includes some standard network security tools, like an intrusion detection system that watches out for unauthorized exfiltration of data. And it has some rather non-standard components – like an alert if a person searches his computer for something surprising.

“Each user searches their own file system in a unique manner. They may use only a few specific system functions to find what they are looking for. Furthermore, it is unlikely a masquerader will have full knowledge of the victim user’s file system and hence may search wider and deeper and in a less targeted manner than would the victim user. Hence, we believe search behavior is a viable indicator for detecting malicious intentions,” Stolfo and his colleagues write.

In their initial experiments, the researchers claim, they were about to “model all search actions of a user” in a mere 10 seconds. They then gave 14 students unlimited access to the same file system for 15 minutes each. The students were told to comb the machine for anything that might be used to financial gain. The researchers say they caught all 14 searchers. “We can detect all masquerader activity with 100 percent accuracy, with a false positive rate of 0.1 percent.”

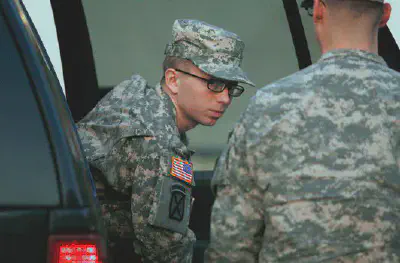

Grad students may be a little easier to model than national security professionals, who have to radically alter their search patterns in the wake of major events. Consider the elevated interest in al-Qaida after 9 / 11, or the desire to know more about WikiLeaks after Bradley Manning allegedly disclosed hundreds of thousands of documents to the group.

Other Darpa-backed attempts to find a signature for squirrely behavior are either just getting underway, or haven’t fared particularly well. In December, the agency recently handed out $9 million to a Georgia Tech-led consortium with the goal of mining 250 million e-mails, IMs and file transfers a day for potential leakers. The following month, a Pentagon-funded research paper (.pdf) noted the promise of “keystroke dynamics – technology to distinguish people based on their typing rhythms – [which] could revolutionize insider-threat detection. " Well, in theory. In practice, such systems’ “error rates vary from 0 percent to 63 percent, depending on the user. Impostors triple their chance of evading detection if they touch type.”

For more reliable results, Stolfo aims to marry his misbehavior-modeling with the decoy documents and with other so-called “enticing information.” Stolfo and his colleagues also use “honeytokens” – small strings of tempting information, like online bank accounts or server passwords – as bait. They’ll get a one-time credit card number, link it to a PayPal account, and see if any charges are mysteriously rung up. They’ll generate a Gmail account, and see who starts spamming.

Most intriguingly, perhaps, is Stolfo’s suggestion in a separate paper (.pdf) to fill up social networks with decoy accounts – and inject poisonous information into people’s otherwise benign social network profiles.

“Think of advanced privacy settings [in sites like Facebook] where I choose to include my real data to my closest friends [but] everybody else gets access to a different profile with information that is bogus. And I would be alerted when bad guys try to get that info about me,” Stolfo tells Danger Room. “This is a way to create fog so that now you no longer know the truth abut a person through this artificial avatars or artificial profiles.”

So sure, Fog Computing could eventually become a way to keep those Facebooked pictures of your cat free from prying eyes. If you’re in the U.S. government, on the other hand, the system could be a method for hiding the truth about something far more substantive.