Intel announces it's built a better microprocessor

Superchip can boost video, graphics of personal computers

by Tom Abate, Chronicle Staff Writer

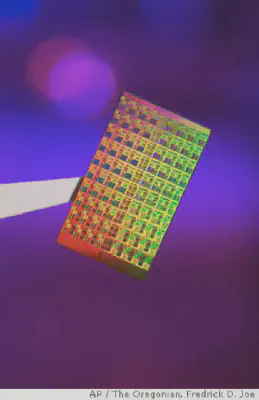

Scientists at Intel Corp. have made an experimental microprocessor the size of a fingertip that has the same computational power that it took a 2,500-square-foot supercomputer to deliver just 11 years ago.

The new chip could give personal computers extraordinary capabilities that are now available to only a handful of research computers, such as video games that look as realistic as television shows and machines capable of understanding speech.

The announcement follows a series of different chip advances by Intel, IBM and Hewlett-Packard, all touting different ways that firms are trying to make processors smaller, faster and more energy-efficient in order to bring better graphics and sound to desktop and, ultimately, handheld devices.

Intel Chief Technology Officer Justin Rattner formally introduced the super-processor Sunday on the opening day of an international conference of chip scientists who will be meeting in San Francisco through Thursday. He said it could take five years before the super-processor is ready for commercial use.

In an advance briefing last week, Rattner used the super-processor to perform more than a trillion mathematical calculations per second. To put that into perspective, it would take light, traveling 186,282 miles per second, 62.1 days to travel a trillion miles.

The trillion calculation threshold – called a “teraflop” – was a big deal a decade ago, when supercomputers first achieved it. Today, the scientific computers that tackle big computational problems like global warming have gone on to even faster speeds. But the excitement here is the prospect of bringing teraflop performance to business and ultimately consumer machines.

“We’re going to put supercomputer-like capabilities onto a single chip at the desktop,” Rattner said.

Jim McGregor, semiconductor analyst for the market research firm In-Stat, said Intel engineered this super-processor to draw roughly the same electricity as today’s PC microprocessors, which will mean that it should be easier to incorporate into future PCs without having to redesign the cooling systems that keep machines from overheating.

“To create supercomputer capability at that low power consumption is stunning,” McGregor said, adding: “But there are still a lot of hurdles to overcome.”

Foremost among these will be the need to create new software capable of directing these super-processors. To understand that challenge, it’s necessary to consider how Intel’s new super-processor differs from today’s microprocessors.

Think of the microprocessor as a brain. For years, chipmakers made these silicon brains faster by shrinking the size of the transistors that form their fundamental working unit. More transistors in the same space offered greater computing capability. Moore’s Law, named after Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, predicted that this dynamic would continue at a steady rate. But as transistors have gotten tinier and tinier, chipmakers have started to have more and more trouble continuing the shrinking act.

Intel’s new super-processor takes a radically different approach to boosting performance. It doesn’t mess with the size of the transistor.

Instead of thinking of the processor as a single brain, they designed it as 80 computing cores. Each core is like a mini-microprocessor, trained to do a small part of some larger task. Intel scientists are using special software algorithms to break huge computational problems into many small pieces – and then using the 80 cores to solve these bits of the problem, all at the same time – to achieve the milestone of a trillion calculations per second. This type of divide-and-conquer problem-solving is called parallel processing. It has been used for years to control house-size supercomputers. In 1996, for instance, Intel built the first supercomputer to hit the trillion-calculation threshold. It was a parallel processor. But it was huge, consisting of 104 computer cabinets that filled a 2,500-square-foot room.

The parallel processing software that ran these room-size supercomputers was written from scratch, said David Bader, executive director of high-performance computing at Georgia Tech.

That was fine when creating a climate-modeling program for a research lab. But Intel’s super-chip is designed for use in ordinary electronic devices, and so its software will have to be written by regular programmers, Bader said. And they will have to rethink how they do things to take advantage of the 80 cores.

“The average programmer is trained to think sequentially, but they are going to have to learn to see tasks in parallel,” said Bader.

The Redwood City startup Rapport, Inc. is another semiconductor firm that has created a high-performance chip by dividing it into many cores. Rapport president Frank Sinton said his company’s chips are designed to deliver low power consumption and high performance, and are currently intended for mobile devices.

“People want more video, better-quality audio, faster speeds and longer battery life,” Sinton said. Designing a single chip to behave like a cluster of processors is a good way to do this – provided software exists to efficiently divide the tasks.

“We are experts in programming,” Sinton said.

While briefing reporters last week, Intel’s Rattner said his company has been working to develop software tools to make parallel processing easier while at the same time trying to get code-warriors thinking about possible uses for these forthcoming super-chips.

“We’re trying to turn on programmers to the fact that this kind of power is coming,” he said.