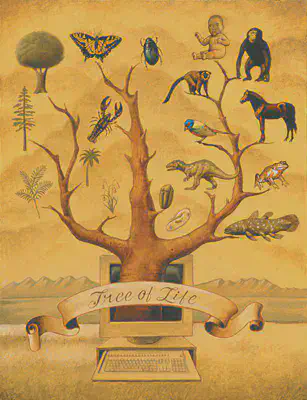

Reconstructing the Tree of Life

Researchers build an essential organizing tool for the future of biology.

by Greg Johnston

Biologist Terry Yates distinctly remembers a question posed in 2000, when he served as director of the Division of Environmental Biology at the National Science Foundation, NSF. About a month after he started his work at NSF in Arlington, Virginia, Director Rita Colwell called a division directors’ retreat to pose a challenge: “Give me your craziest idea that would represent a major unmet need for the nation or the world.”

Yates, now vice president for research and economic development at the University of New Mexico, responded. “I said, ‘I think it’s about time we try to assemble a universal Tree of Life, from microbes to mammals.’ I thought I’d get laughed out of the place until I heard responses like ‘I think that’s a good idea. Our program can’t go any further because we don’t know what organisms to sequence next.’” By reconstructing the Tree of Life, researchers and scientists would have a clearer picture of how life has evolved and continues to evolve.

There are an estimated 1.7 million known species of life on Earth. “This tree can be a pretty powerful predictive tool,” says Yates. “But there is a whole computational infrastructure that has to be done—not just the machines, but also software that is more efficient and faster. To assemble a tree that has 1.7 million branches on it, computationally and in any sensible way, is going to take enormous computer power.”

Yates’ idea gave rise to the NSF “Assembling the Tree of Life” research program, which funds the collection and analysis of extensive data on modern and fossil species. NSF also ran the Information Technology Research, ITR, program, a goal of which was to foster large-scale applications of information technology to new areas of science.

At the UNM School of Engineering, Professor Bernard Moret and Associate Professor David Bader had already received several ITR grants to support their work in computational phylogenetics—algorithms to reconstruct evolutionary trees such as the Tree of Life. Moret and Bader each hold joint appointments in the Departments of Computer Science and Electrical and Computer Engineering. Collaborating with Professor Tandy Warnow at the University of Texas-Austin, they led a group of biologists and computer scientists in a proposal to ITR to build a program called Cyber Infrastructure for Phylogenetic Research, CIPRES, needed to support the reconstruction of the Tree of Life.

In September 2003, NSF announced that CIPRES, one of only seven proposals funded out of more than seventy submitted, would receive a five-year, $11.6 million grant. CIPRES is a collaboration of thirteen institutions, including three museums. Lead institutions are UNM, UT-Austin, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at San Diego, and Florida State University.

Moret, director of the CIPRES project, is known primarily for his work in algorithm engineering. He has gained extensive expertise in recent years in computational biology. For the Tree of Life, Moret leads a team of over thirty-five computer scientists, biologists, and mathematicians, including students and postdoctoral researchers.

“What the Table of Elements did for chemistry, the Tree of Life will do for biology,” says Moret. “It’s a fundamental organizing tool. Thus, while the Tree of Life is an abstract pursuit, it will help develop a deep understanding of mechanisms and models that are going to be used everywhere in biology and medicine.”

Moret’s closest collaborator at UNM is David Bader. Bader’s research interests lie in computational biology, genomics, high-performance computing, and parallel computation. Bader is teamed with Fran Berman, director of the San Diego Supercomputing Center, which is the physical location for the computational infrastructure. Bader and Berman will lead the CIPRES efforts in high-performance computing.

Moret and Bader have already achieved spectacular results by applying algorithm engineering and parallel computing to problems in phylogeny. In 2000, a team including Professor Robert Jansen from UT-Austin reconstructed the phylogeny of thirteen members of the bluebell family of flowering plants, an adaptable family found throughout the world.

At the time, existing approaches would have required several centuries of computation on a high-powered workstation to reconstruct the evolution. However, Moret and Bader developed new code and used a UNM computing cluster of 512 processors at the Center for High Performance Computing to carry out the analysis in just one pass. Continuous refinement of the code at UNM now enables the same analysis to be run in thirty minutes on a laptop, a tremendous improvement for a process that must examine nearly fourteen billion candidate trees.

The research focused on only thirteen plants. Biologists estimate that there are anywhere from ten to a hundred million undescribed species beyond the identified 1.7 million known species of living organisms. “We will need to run billions of trillions times faster than we can run today,” says Moret, “and that cannot be done through hardware technology alone.”

“Building the Tree of Life is a problem for the next few decades,” explains Bader. “So many computing cycles and so much research are directed at this problem because it has direct impact on our future, but it will take time to accumulate the data and the know-how.”

The effort will be international: CIPRES has collaborators in Europe, Asia, Oceania, and South America. For the Tree of Life to be successful, extensive collaboration will also need to occur between computer scientists and biologists. “We want to make sure that what we deliver over the next five years is of direct use to biologists—an infrastructure that has been thoroughly tested,” Moret says. “We must understand in detail the performance characteristics of our algorithms, not just in terms of running time—that’s the easy part—but more importantly in terms of accuracy under the models of evolution that the biologists are interested in. There is only one Tree of Life—we must get it right.”

By the end of the five-year grant cycle, Bader says CIPRES will have built a computer platform allowing biologists worldwide to go to a Web site, enter data, select methods, and have their analysis carried out. The more computing-oriented scientists can choose to download the software package and run it on their own machines.

Yates uses an analogy to describe the collaboration between two scientific communities. “Mother Nature has given us almost two billion years of free research and development. These are time-tested and thoroughly validated software packages. All we have to do now is run them through the computer and they will tell us what to do.”